Population growth

Recently I came across the following quantitative question:

A mythical city contains \(100,000\) monogamously married couples but no children. Each family wishes to “continue the male line”, but they do not wish to overpopulate. So, each family has one baby per annum until the arrival of the first boy. For example, if (at some future date) a family has five children, then it must be either that they are all girls, and another child is planned, or that there are four girls and one boy, and no more children are planned. Assume that the children are equally likely to be born male or female. Let \(p(t)\) be the percentage of children that are male at the end of year \(t\). How is this percentage expected to evolve through time?

At this point, the ambitious reader should not avoid spoilers and take a few minutes to try to solve it without using a piece of paper for calculations (ideally). If you do any mathematics whatsoever, you probably are missing the point.

A few additional assumptions, if unclear:

- Consider that no person in the city dies.

- The kids will not become parents themselves during the time horizon of the analysis.

- The marriages remain fixed.

Naive Intuition

When we consider a short time horizon, we can easily imagine large families that have many daughters and a single son, thus there must be more girls than boys. Additionally, at a longer time horizon, most families would be expected to have a boy and stopped having more kids. We could conclude then that the percentage of male children is small at the beginning and slowly increase over time, never exceeding \(50\%\).

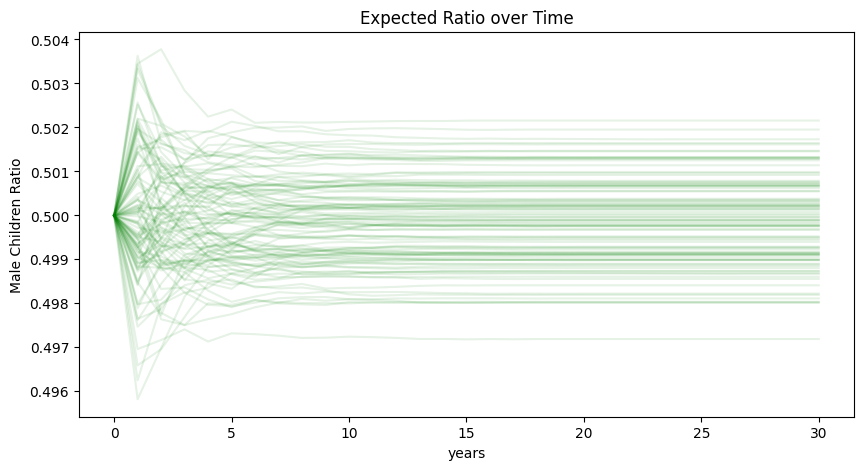

Simulation

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.figure(figsize = (10, 5))

# Repeat experiment multiple times

tries = 100

for _ in range(tries):

np.random.seed()

available_couples = 100000 # Couples who did not have a boy yet

male_cumulative = [0] # Cumulative male children per year

female_cumulative = [0] # Cumulative female children per year

ratio = [0.5]

years = [0]

# Run growth simulation for a fixed time horizon

total_years = 30

for t in range(total_years):

years.append(t+1)

if available_couples == 0:

male_children = 0

female_children = 0

else:

male_children = np.random.binomial(available_couples, 0.5)

female_children = available_couples - male_children

available_couples -= male_children

male_cumulative.append(male_children + male_cumulative[-1])

female_cumulative.append(female_children + female_cumulative[-1])

ratio.append(male_cumulative[-1]/(male_cumulative[-1] + female_cumulative[-1]))

plt.plot(years, ratio, alpha=0.1, color='g')

plt.xticks(range(0,len(years), 5))

plt.xlabel('years')

plt.ylabel('Male Children Ratio')

plt.title('Expected Ratio over Time')

plt.show()

So, what exactly went wrong?

The number of large families is surprisingly small!

Analysis

The key word in the problem statement is expected. No real calculation is needed to see that at each time step an equal number of female and male babies are expected be born. Therefore, the proportion of male and female children is expected to remain at \(50\%\).

Any doubts?

Mathematical arguments must ultimately convince the reader. Let us consider the number of female children within each family as an independent random variable \(f_i\), where \(1 \leq i \leq 10^5\). By the problem statement, \(f_i\) follows a geometric distribution with success probabiliy \(p=0.5\). Thus, the probabiliy of having \(k\) girls before a boy is given by \(P(f_i = k) = (1-p)^k p\). The mean of this distribution is given by \(\frac{1-p}{p}\), which in our case is \(1\). In other words, in average each family will have one boy and one girl.

Finally, by linearity of expectation, we can observe that for the whole population the expected ratio of male to female children remains at \(50\%\).

Conclusion

It is very easy to have the wrong intuition about simple statistical concepts, even for a person with good working knowledge of statistics. Consider the case where one needs to examine evidence and make decisions for a complex model of reality, how likely are we to have an appropiate intution? It is really key to study simplified cases to build up our intuitive reasoning. Even small tweaks into seemingly simple models can create insanely complex behaviors (e.g. Rule 30).

One thing to notice is that most people tend fo focus on extreme behvior of each family, rather than the general trend of the population growth. Moreover, regardless the intention of each family to have boys (specified by the stopping rule), this only affects the size of one family, not the male ratio within the population.

References

Acknowledgment

Thanks to Brigitte Castañeda, Anji Yi, John Pang, and Aleksandra Galitsyna for the constructive feedback and hightling a few clarifications on the problem statement.