Bingo

Contrary to most of the nonsense conversations I have on a daily basis, this one presented a reasonable opportunity to delve into. Nostalgia took me back to 2008-2010 (I know what you are thinking!), during my last years of high school. We had the tradition of playing BINGO during the school anniversary festivities. Vividly recall the day when I thought I had won a smaller prize with the “O” pattern: only to realize I had one mistake, unfortunately.

Despite I never won myself the maximum prize (around $2000), attributed to the first player completing the whole board, I witness the excitement of lucky people walking among a big crowd towards the presenter to verify their victory. Among those memories, the following questions appeared in my mind: How difficult was actually to win, afterall? Is it a worthy investment? Is it actually easier to win forming the “N” pattern? Ergo, this post.

Game Description

The U.S. 75-ball bingo game consists of disposable paper cardboards which contain a unique combination of 25 numbers on squares arranged in five vertical columns (corresponding to each of the BINGO letters) and five side to side rows. Each space is covered except the center one, which is free space. The range of printed numbers that can appear on any order on the card is restricted by column. In particular, the column ‘B’ only contains numbers between 1 and 15 inclusive, the column ‘I’ only contains numbers between 16 and 30 inclusive, and so on.

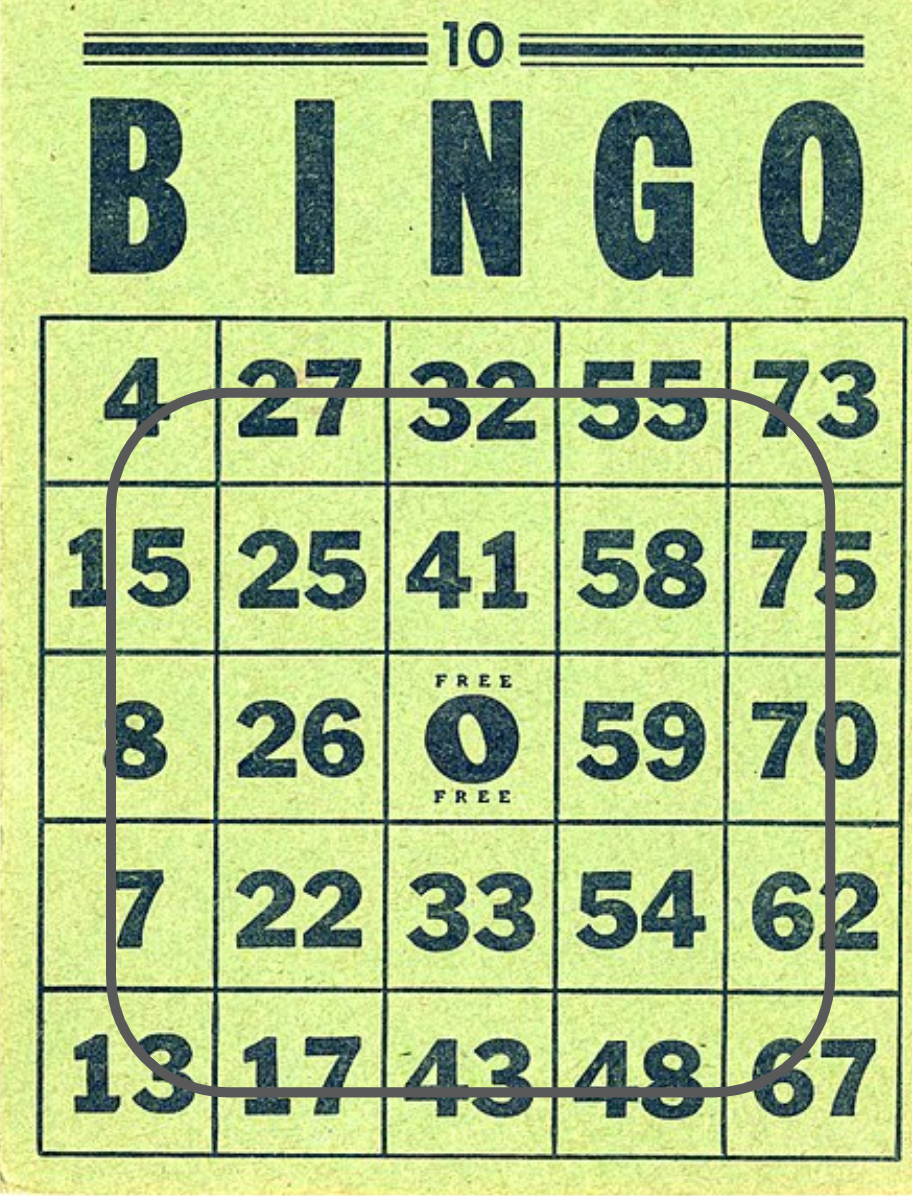

Each of the 75 possible numbers is randomly drawn by a presenter of the game, while each player marks the announced number down on their BINGO card, until a winner is revealed within the audience. The most common winning scenario is a full cover pattern. That is, when each of the 24 numbers is marked on a cardboard, its owner can claim BINGO. This is usually assigned to the highest prize of the event. Other winning scenarios consist of forming particular patterns of marked cells in the board. For example, forming a letter ‘O’ with a fraction of the marked cells. That would require all the numbers in the columns ‘B’ and ‘O’, as well as the first and last elements of each column, to be marked as the picture below shows.

Analysis

Let us define the following variables

- \(X\), number of draws so far

- \(\mathcal{F}\), random event of winning with full cover pattern.

- \(\mathcal{B}\), random event of winning with “B” pattern.

- \(\mathcal{O}\), random event of winning with “O” pattern.

- \(\mathcal{N}\), random event of winning with “N” pattern.

Full Cover Probability

The cumulative probability of winning with a full cover board in less or equal than \(D\) draws is,

\[\mathbb{P}_F ( X \leq D ) = \frac{\binom{51}{D-24}}{\binom{75}{D}}\]The distribution has support only for values \(D\geq 24\). Thus,

\[\mathbb{P}_F[ X = D ] = \mathbb{P}_F[ X \leq D ] - \mathbb{P}_F[X \leq D-1]\] \[\mathbb{P}_F[ X = D ] = \frac{24\binom{51}{D-25}}{ (D-24)\binom{75}{D-1}}\]Pattern Probability

The cumulative probability of winning with a particular pattern \(P\) in less or equal than \(D\) draws is given by

\[\mathbb{P}_P ( X \leq D ) = \sum_{i=P_{size}}^{24} \frac{\binom{24}{i}\binom{51}{D-i}}{\binom{75}{D}} \times \text{Probability of Forming Pattern P with i marked numbers}\]In particular, we have for patterns \(\mathcal{N}, \mathcal{O}\) and \(\mathcal{B}\) the following expressions,

\[\mathbb{P}_B ( X \leq D ) = \sum_{i=12}^{24} \frac{\binom{24}{i}\binom{51}{D-i}}{\binom{75}{D}} \times \frac{\binom{12}{12}\binom{12}{i-12}}{\binom{24}{i}} = \sum_{i=18}^{24} \frac{ \binom{12}{i-12}\binom{51}{D-i}}{\binom{75}{D}}\] \[\mathbb{P}_O ( X \leq D ) = \sum_{i=16}^{24} \frac{\binom{24}{i}\binom{51}{D-i}}{\binom{75}{D}} \times \frac{\binom{16}{16}\binom{8}{i-16}}{\binom{24}{i}} = \sum_{i=16}^{24} \frac{ \binom{8}{i-16}\binom{51}{D-i}}{\binom{75}{D}}\] \[\mathbb{P}_B ( X \leq D ) = \sum_{i=18}^{24} \frac{\binom{24}{i}\binom{51}{D-i}}{\binom{75}{D}} \times \frac{\binom{18}{18}\binom{6}{i-18}}{\binom{24}{i}} = \sum_{i=18}^{24} \frac{ \binom{6}{i-18}\binom{51}{D-i}}{\binom{75}{D}}\]Probability Distributions

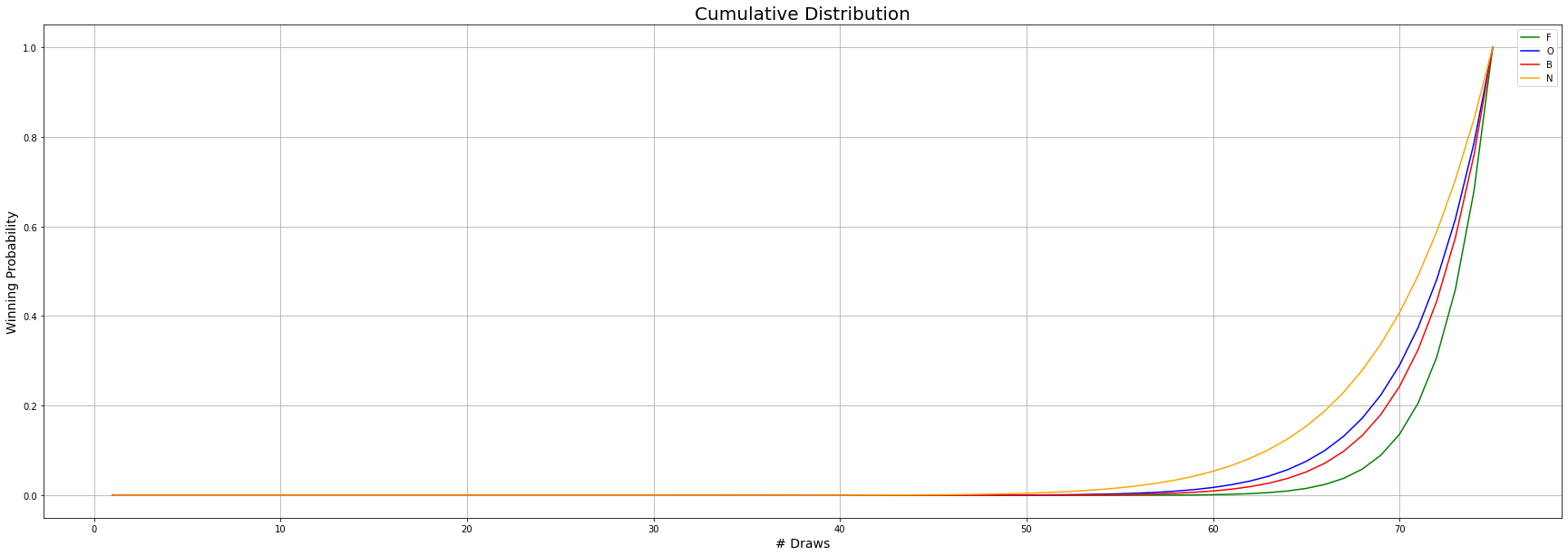

We can visually inspect how the cumulative distribution probabilities for the different winning cases look like. We can notice that only after \(60\) draws the chances stop being negligible. This explains why the game lasts that long without winner, even for simpler patterns.

One interesting observation is how close the probability curves are from each other, defying our initial intuition. We expected that winning by full cover represented a much slimmer chance than by an \(\mathcal{O}\) pattern, for instance. Yet, we observe that at \(70\) draws one has around \(0.15\) probability of winning by full cover vs. a \(0.3\) probability of winning by \(\mathcal{O}\) pattern, if playing in isolation.

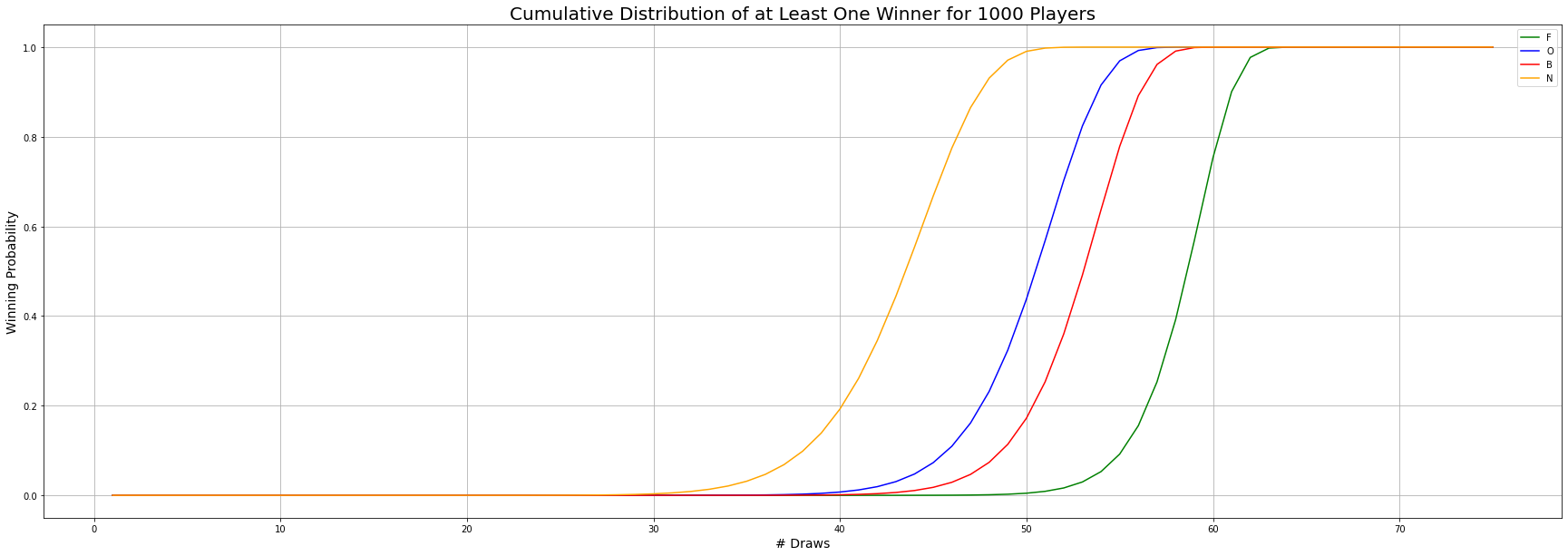

However, in the most realistic BINGO setting we have a huge crowd (\(N\sim 1000\)) so we care about the probability of at least one person winning given \(X\) draws so far. Thus, we proceed to obtain the cumulative probability distributions of at least one person winning for each pattern.

If the probability of an event happening is \(p\), then the probability that it will happen at least once in \(N\) times is \(1 - (1-p)^N\). Using this formula, we obtained the following results,

The updated results match our intuition: where each cumulative probability curve is drastically spread after \(\sim 40\) draws. From these distributions we can calculate the expected value of draws required to win for each case.

| Pattern | Expected Draws To Win - 1 player | Expected Draws To Win - 1k players |

|---|---|---|

| Full Cover | 72.96 | 58.79 |

| B | 72.00 | 53.16 |

| O | 71.52 | 50.56 |

| N | 70.15 | 43.56 |

Finally, this analysis leads to another open question for the curious reader: what would be the ‘optimal’ way of assigning the prizes’ values given our probabilistic findings?

I am confident that my high school BINGO’s organizers did not think this thoroughly nor did the math. Since \(\mathcal{N}, \mathcal{O}\) and even \(\mathcal{B}\) were given kitchen appliances or TVs as prizes, while the full cover win was rewarded with the highest prize of 2000 dollars, for a 3 dollar BINGO board.

References

- Blog post on Bingo Calculations - link

- Blog post on Computation of Bingo Probabilities Numerically - link

Acknowlegdments

Thanks to Maximilian Montserrat for engaging conversations and running the numerical calculations code to verify results.